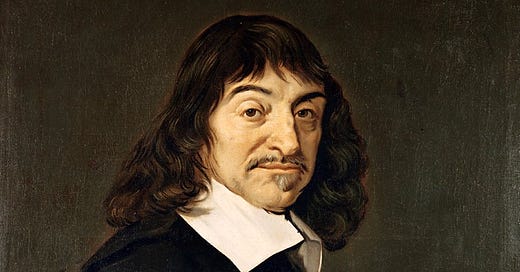

Cogito, ergo Sum. These immortal words shifted the trajectory of philosophy and laid the groundwork for Cartesian dualism. René Descartes stands as a cornerstone of modern philosophy. The statement itself can be interpreted as a statement of self-evident truth or a performative utterance. Alternatively, it can be viewed as an inference—a conclusion drawn from a process of rational reflection. In this paper, I aim to defend Descartes' cogito as an inference rather than a mere performance, highlighting the logical steps and philosophical context that underpin this interpretation.

For the sake of brevity, I will not be addressing the issues of the matrix or the existence of other people. Also, given the extensive scholarly writing and research that has been performed on this subject, I will not be producing any new philosophical revelation or thesis. If I did, I would hope to see this paper published. I intend to demonstrate that the cogito is best understood as an inference rather than a performance.

Firstly, it's crucial to understand the philosophical backdrop against which Descartes formulated his cogito. In his quest for undeniable knowledge, Descartes embarked on a radical methodological doubt, questioning the reliability of sensory perception and even the existence of an external world. This skeptical inquiry aimed to strip away all beliefs that could be doubted, leaving only what is certain. In this context, the cogito emerges not as a spontaneous assertion but as a deliberate philosophical reflection.

Descartes begins his Meditations on First Philosophy by doubting everything, including the existence of an external world and the trustworthiness of sensory experience.

“Some years ago I was struck by how many false things I had believed, and by how doubtful was the structure of beliefs that I had based on them. I realized that if I wanted to establish anything in the sciences that was stable and likely to last, I needed—just once in my life—to demolish everything completely and start again from the foundations.” (Meditations on First Philosophy 1)

Throughout the meditations, and the subsequent Discourse on the Method, Descartes realizes that even in doubt, there must be a doubter—a thinking entity. This realization forms the basis of the cogito or the undeniable fact of one's own thinking.

“[B]ecause all the mental states we are in while awake can also occur while we sleep ·and dream·, without having any truth in them. But no sooner had I embarked on this project than I noticed that while I was trying in this way to think everything to be false it had to be the case that I, who was thinking this, was something And observing that this truth I am thinking, therefore I exist was so firm and sure that not even the most extravagant suppositions of the sceptics could shake it, I decided that I could accept it without scruple as the first principle of the philosophy I was seeking.” (Discourse on the Method 16)

The reason why the debate over the cogito being a performance or inference is due to the nature of the existential reality that Descartes creates using the word cogito. Jeffrey Tlumak offers a more detailed explanation. “1. The Cogito is a truth-professing performative, specifically, an enactment which is self-affirming or self-verifying, a semantically-contentful activity whose very occurrence inescapably provides immediate and conclusive evidence that what it says is true.

3. The Cogito is an inference. But it is clear that this cannot mean it is a syllogistic inference. […] Descartes insists repeatedly that such major premises in philosophy are precisely what is centrally in dispute, so cannot be a starting point when following the analytic method of discovery.” (Tlumak 24-25)

I do think it is important to remember the process of logical reasoning and induction. An inference is an argument leading from a premise to a conclusion. Notably, the cogito, ergo sum is an inferential argument. Although this is straightforward and a rather superficial, way of understanding the function of the cogito, it is important to remember the purpose of language. Latin, compared to English or French is rather straightforward. Unlike these languages, it does not have definite articles. Thus, translations of cogito ergo sum are not as precise in capturing the idea behind the cogito and how it functions.

An important aspect of the cogito is that it is not a brute assertion but rather a conclusion drawn from a process of rational inference. Descartes does not simply state "I am," but rather reasons that because he doubts, he must exist as a thinking being. This inference follows a logical pattern: doubting presupposes thinking, and thinking presupposes existence. Thus, the cogito is the necessary conclusion of Descartes' skeptical doubt.

Descartes’ skeptical doubt originates from the idea that the senses can deceive. Descartes’s methodological skepticism enabled him to systematically question whether certain beliefs, such as his own existence are true or real. Yet, the idea that one can be deceived insists that one must exist. As noted in the previous paragraph, the cogito becomes a necessary conclusion of Descartes’ skepticism because thinking is an essential quality of Descartes’s philosophy. The cogito infers the thinking of an individual.

Prima facie, the statement cogito ergo sum appears circular. Although circular arguments are not persuasive, they are considered valid arguments. The main objection to this is the idea that Descartes already assumes that the self exists by stating that the self is thinking. One way that Descartes could potentially evade circularity is by doubting his existence and then assuming there is some level of thinking happening. This thinking would take a Berkeley route because Descartes would have to assume that God is the one doing the thinking that is causing his existence.

Descartes was aware this was an issue facing the cogito. Critics often argue that the cogito is circular or trivial, but such objections misunderstand its philosophical significance. Although it may seem circular to prove one's existence through one's own thinking, Descartes' aim is not to establish the existence of a particular entity but to ground all knowledge in the certainty of the self. The cogito serves as the bedrock upon which Descartes builds his philosophical edifice, providing a firm foundation for the pursuit of truth.

I think Descartes is attempting to achieve an existential statement. This existential statement pertains to the idea of thinking and existence. As Julius Weinberg writes, “The purpose of the cogito was to establish the existence of something.” (489) The fundamental aspect of Descartes’s philosophy, and his subsequent system of skepticism, is the first principle of the cogito. Given the cogito is the first principle of Descartes’s philosophy, then it follows that the cogito establishes the first existence.

“The existence thus established can be called the principle from which other existents are deduced.” (Weinberg 489)

Furthermore, this establishment of the first principle serves as Descartes’s basis of knowledge and as a way for an individual to navigate the world around them. The inference of the cogito facilitates an epistemology and metaphysical grounding of the world while making the statement of “I exist” not existentially ambiguous. I think, therefore I exist, is tautological in the sense that “I” is an existential quantifier. Essentially, it is presupposing its own existence, and in a sense can be formulated as: “there exists an I, which performs the function of thinking, and therefore that I exists”. When written this way, the tautology is clearer. For Descartes, solidifying the first principle of the cogito is the most important aspect of his philosophy.

It can be argued that doubt is the real first principle of Descartes’s philosophy because it provides a better fundamental reflection of his principle. In this sense, thinking would be a subordinate function to doubting because doubting that you know something is still doubting. Alas, the cogito is the first principle. Descartes' cogito serves as the foundation upon which he reconstructs his system of knowledge. From the certainty of his own existence as a thinking being, Descartes proceeds to establish the existence of God and the external world, ultimately laying the groundwork for his epistemology and metaphysics. Without the cogito as a starting point, Descartes' entire project would collapse, highlighting its significance as an inference rather than a mere performance.

“The cogito of Descartes seems to be clearly an argument or inference in the light of three doctrines: (1) the mind knows itself directly, (2) existence is a “perfection” (3) necessary conditions of simple natures or notions are among the things assumed by Descartes.” (Weinberg 490)

Now that I have presented my reasoning, and the reasoning of others who support the inferential argument, I will focus my attention on one of the lengthiest papers that has been written on this subject. For brevity, I will not analyze each part of the paper. Rather, I will focus on the key differences in argument and respond to them while being charitable. Jaakko Hintikka wrote a piece arguing that Descartes’s cogito is performance rather than an inference. I will be focusing on his idea of the cogito and the function of the sum.

There are certain caveats of the cogito that should be addressed. Jaakko Hintikka’s paper, “Cogito, Ergo Sum: Inference or Performance?” helps elucidate the issue of the cogito. “Descartes realized that his cogito argument deals with a particular case, namely with his own.” (Hintikka 20) The nature of the cogito is not focused on a generalized truth like most tend to presuppose, rather it is a specific case for a specific person. Namely, the person who utters the statements, “I do not exist” or “I exist.”

Throughout this paper, Hintikka argues that Descartes’ cogito ergo sum is a performance rather than an inference. Hintikka’s argument centers around the idea that the cogito is logically and existentially inconsistent. “Descartes realized, however, dimly, the existential inconsistency of the sentence “I don’t exist” and therefore the existential self-verifiability of “I exist.” Cogito, ergo sum is only one possible way of expressing this insight. Another way employed by Descartes is to say that the sentence ego sum is intuitively self-evident.” (Hintikka 15) For reference, Hintikka defines existential inconsistency as p is existentially inconsistent for the person referred to by a to utter if and only if […] p; and a exists” (in the ordinary sense of the word).” (11)

Furthermore, Hintikka argues that existential inconsistency is thus a performative character that is exactly in the same sense as that of the existentially inconsistent statements. Descartes does not demonstrate the indisputability of the sentence “I am” by merely deducing sum from cogito. Rather, as Hintikka suggests, Descartes realizes that this indisputability of “I am” is the result from the act of thinking. It seems that Hintikka recognizes the importance of consciousness as the foundation of human experience. Although it may appear existentially inconsistent prima facie, I think the “I am” statement can be understood as affirming the first principle.

“In Descartes’s argument the relation of cogito and sum is not that of a premise to a conclusion. Their relation is rather comparable with that of a process to its product.” (Hintikka 16)

At first glance, this interpretation might seem counterintuitive, as Descartes' statement appears to present a logical inference: the act of thinking necessarily implies the existence of a thinking entity; however, Hintikka's insight invites us to delve deeper into the nature of the cogito and its implications.

If we consider the cogito not as a logical argument but as a process—a dynamic, ongoing activity of thinking—then the "sum" or "I am" becomes more than just a conclusion; it becomes the continual outcome of this process of thinking. In this light, the cogito is not merely a static starting point leading to a fixed conclusion, but rather an ongoing process of self-awareness and self-realization.

Moreover, Hintikka's interpretation highlights the inseparable link between thinking and being. The act of thinking is not just evidence of existing; it is constitutive of existence itself. In continuously engaging in the process of thought, the thinking self reaffirms its own existence moment by moment. This perspective also underscores the existential dimension of Descartes' assertion. Existence is not merely a static state but an ongoing process of self-awareness and consciousness. Through the continual exercise of thought, the thinking self continually reaffirms its existence, perpetuating the dynamic relationship between "cogito" and "sum."

In response to Jaakko Hintikka’s paper, philosopher Harry Frankfurt wrote in defense of the inferential argument against Hintikka. Concerning Hintikka’s definition of an existential inconsistency, Frankfurt writes: “There is, however, a more interesting difficulty in what Hintikka says about cogito ergo sum as an inference. His point is that the basis of the inference from cogito to sum is the existential inconsistency of “I think, but I do not exist.” This statement is existentially inconsistent because its conjunction with “I exist” is self-contradictory.” (Frankfurt 330)

At the heart of Frankfurt's critique lies the notion of existential inconsistency. In the case of "I think, but I do not exist," the conjunction of "I think" with "I do not exist" leads to an existential contradiction. This contradiction arises because the act of thinking presupposes the existence of a thinking entity; thus, to assert that one thinks while simultaneously denying one's existence is logically nonsensical. Furthermore, Frankfurt points out that the resolution of this existential inconsistency lies not in a logical inference from "cogito" to "sum," but rather in the inherent self-contradiction of denying one's existence while simultaneously engaging in the act of thinking. In other words, the very act of thinking implies the existence of a thinking self, rendering the denial of existence untenable.

Next, Frankfurt criticizes Hintikka’s proposition of the sum. This is one of the best defenses of the inferential argument from Frankfurt. Denial of the sum in a logical sense is not a formal contradiction. “It is the proposition that sum is true whenever he pronounces or conceives it. His conclusion is, in other words, that it is logically impossible for him to pronounce or to conceive sum without sum being true. This conclusion in no way denies, of course, that sum is logically contingent.” (Frankfurt 342)

Frankfurt suggests that Descartes' conclusion is not simply that sum is true whenever he pronounces or conceives it, but rather that it is logically impossible for him to pronounce or conceive "sum" without it being true. This distinction is crucial for understanding the nature of Descartes' argument and its implications for the truth status of sum. Descartes' conclusion, according to Frankfurt, does not assert that sum is true by his pronouncement or conception alone. Instead, it reflects a deeper logical necessity: the impossibility of conceiving or pronouncing sum without it corresponding to reality. In other words, for Descartes, the truth of sum is not contingent upon his subjective thoughts or beliefs but is instead grounded in a fundamental logical necessity.

Moreover, Frankfurt clarifies that Descartes' conclusion does not deny the logical contingency of sum. Although Descartes establishes the necessity of sum being true whenever it is pronounced or conceived, he does not assert that sum is necessarily true in all possible worlds or circumstances. Instead, Descartes' argument highlights the logical impossibility of denying one's existence while engaging in the act of thinking, thus affirming the truth of sum within the context of the cogito.

By emphasizing the logical necessity of sum within the framework of the cogito, Frankfurt sheds light on Descartes' broader philosophical project. Descartes seeks to establish a firm foundation for knowledge and certainty by grounding truth in the undeniable certainty of self-awareness. In doing so, Descartes lays the groundwork for a rationalist epistemology that privileges the certainty of introspection over external sensory experience.

Now that I have covered the Hintikka article and the Frankfurt response, I will begin the conclusion of this paper with a quote by Jeffrey Tlumak that summarizes the importance of the cogito.

“The Cogito is extraordinary in that it exemplifies simultaneously all the ways a foundational certainty can be discovered, indeed, discovered by any attentive inquirer, regardless of antecedent theoretical commitments.” (Tlumak 26)

Descartes' cogito ergo sum is indeed remarkable, as Tlumak aptly notes, for it embodies the multifaceted nature of foundational certainty. Tlumak highlights the extraordinary aspect of the cogito in that it encompasses various avenues through which such certainty can be apprehended, accessible to any diligent seeker of truth, irrespective of their preexisting philosophical frameworks. This observation underscores the universality of the cogito's appeal, transcending philosophical boundaries and theoretical predispositions. Descartes' proposition serves as a beacon of certainty, illuminating the path for all who engage in sincere inquiry, regardless of their starting points or beliefs.

The nature of the cogito and Descartes’s first principle of philosophy will be subject to scholarly reviews for many years to come. Throughout this paper, I have aimed to provide a reasonable defense for believing the nature of cogito, ergo sum to be an inferential argument rather than a performative one. I believe I have been rather successful in this argument and that I have presented the arguments from both sides fairly. The victory will be determined by history, yet I believe Descartes would be slightly humored to learn that philosophers are still debating this topic today.

Descartes' cogito should be understood as an inference rather than a performative utterance. Emerging from a process of systematic doubt and rational reflection, the cogito represents the culmination of Descartes' philosophical journey—a conclusion drawn from the necessity of a thinking self. Far from being a trivial or circular assertion, the cogito serves as the starting point for Descartes' entire philosophical enterprise, providing a solid foundation for the pursuit of knowledge and truth.

The cogito serves as a cornerstone for rational inquiry. Through the cogito, Descartes establishes a point of departure for philosophical investigation, inviting us to explore the depths of our existence and the world around us. The cogito endures as a potent reminder of the power of introspection and reason in the pursuit of truth. As we engage with the complexities of existence, let us not forget the profound insight encapsulated in these three simple words: cogito ergo sum.

Works Cited

Descartes, René. “Descartes1641_1.PDF.” Early Modern Texts,

www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/descartes1641_1.pdf.

Descartes, René. “Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s ...” Early Modern Texts, www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/descartes1637.pdf.

Frankfurt, Harry G. “Descartes’s Discussion of his Existence in the Second Meditation.” The Philosophical Review, vol. 75, no. 3, 1966, pp. 329–356, https://doi.org/10.2307/2183145.

Hintikka, Jaakko. “Cogito, Ergo Sum: Inference or Performance?” The Philosophical Review, vol. 71, no. 1, 1962, pp. 3–32, https://doi.org/10.2307/2183678.

Tlumak, Jeffrey. “Descartes and the Rise of Modern Philosophy.” Classical Modern Philosophy, Routledge, New York, New York, 2007, pp. 1–68.

Weinberg, Julius R. “Cogito, Ergo Sum: Some Reflections on Mr. Hintikka’s Article.” The Philosophical Review, vol. 71, no. 4, 1962, pp. 483–491, https://doi.org/10.2307/2183460.